The trend story headline I can't stand

Plus, the usual niche internet corner and meme roundup.

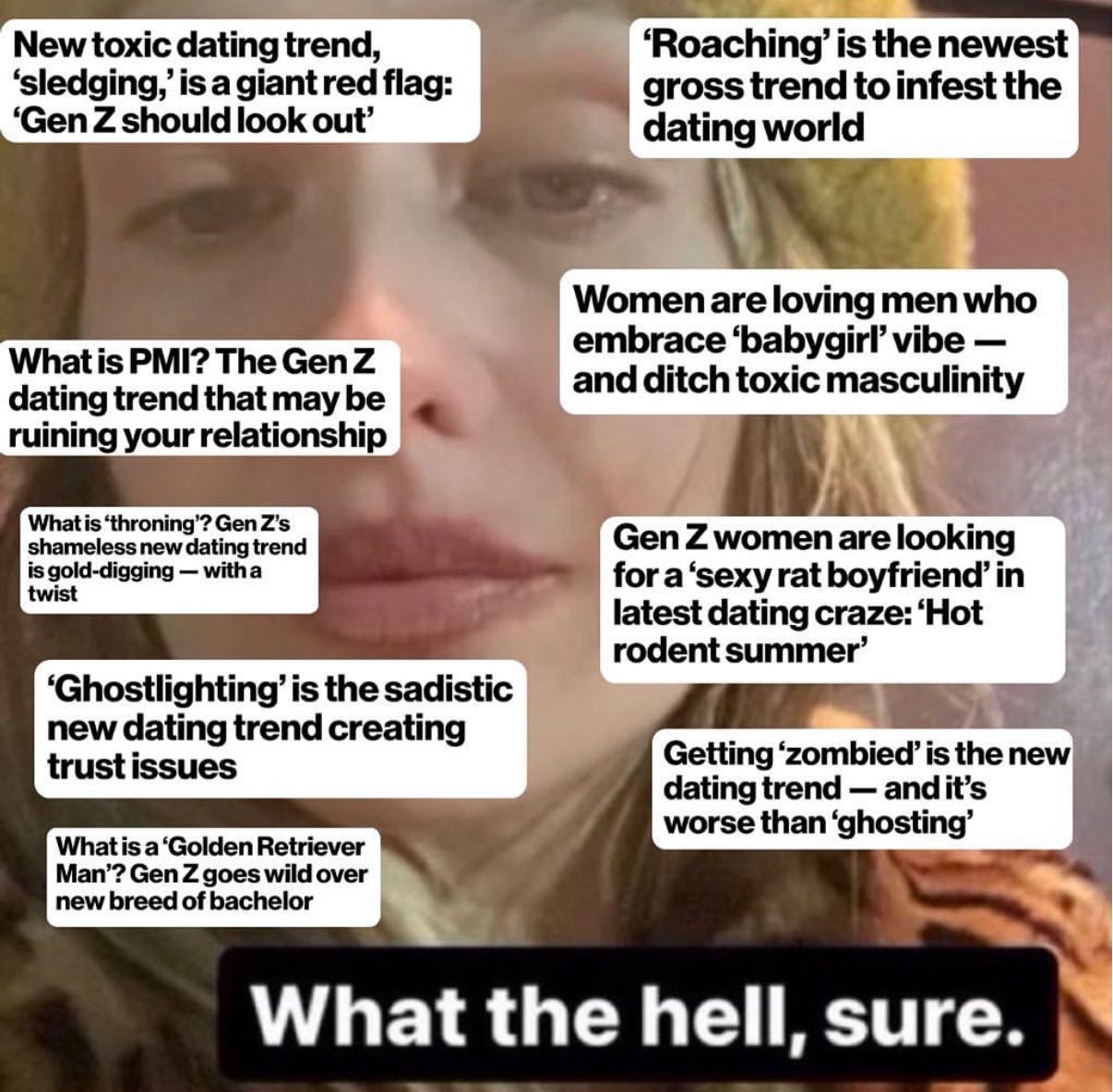

Read enough internet trend reporting and you’ll start to notice a common headline format. It goes something like: “Everyone is ___ now.” Alternatively: Everything is ___ now. Or, phrased as a question: Why is everyone/everything ___ now?

I started to notice this a few years ago, when I was very new to internet and tech journalism. Now it feels like these headlines automatically find me.

Try Googling “everyone is now” and you’ll come across a smattering of examples. Here are a few:

Everyone now: wants to go to college in the South, dresses the same, is unhappy at work, is so rude, wants to go to Maine, is learning to become a personal trainer, has a stack, is traveling to Costa Rica, hates runners, is hating on Instagram, is microdosing Ozempic, has a belted bag, is dating pathological liars, is wearing Salomon shoes, wants to buy candy on TikTok, wants to chop off their hair, is bouldering, owns Adidas Gazelles.

Another popular variation uses the phrase “obsessed with” (or “suddenly obsessed with”). Everyone is obsessed with Diet Coke, traditional decor, food-themed aesthetics, alien beauty, drinking water, ceramics, astrology, dirty sodas, pickleball, buccal fat, liquid rhinoplasties, dopamine, meat sticks and cottage cheese.

I don’t want to come across too high and mighty: I’ve used this format before, many times (and close cousins “___ is dead” and “___ is over”). I’ve pitched stories where, stuck on a potential headline, I defaulted to some version of “Everything is ___ now” or “Why is everyone ____ now?”

Readers are smart, of course. Most can tell when a headline like this is meant to add a bit of harmless dramatic flair rather than declare a definitive fact. It’s also important to note that, depending on the outlet, journalists don’t always or even usually write their own headlines. And even when they do, many want to dig into a trend with more analysis, context, and original reporting than they’re given the time, word count, editorial flexibility, and resources to do.

I also think that “Why is everyone [I know] suddenly doing this?” can be a great framework to start reporting out a potential story, if not necessarily the headline. It probably wasn’t that much of a stretch to say that “everyone” was baking sourdough in 2020. And there are tech phenomena that feel all-encompassing: it does seem like every social media app wants to be TikTok, or that every productivity tool is piling on the AI features.

But on the whole, I think these headlines contribute to a trend reporting landscape centered around the fleeting over grounded analysis.

Editors often give newer journalists the following feedback: “Give me a story, not a topic.” It’s good advice: you can’t just point something out, you need to explain why it matters and is relevant to readers. At the same time, I think this can produce overfitting, resulting in trend stories that oversell how influential a specific shift or trend is. It contributes to an insular media landscape that produces 44 of the same articles on Dimes Square or a rotating cast of 15 writers/influencers/media personalities who seem to just take turns interviewing each other.

Trend Reporting 101 trains you to think in the “rule of three": It’s a trend once you’ve seen it three times. In fashion journalism, that might mean seeing something on the runway, on a celebrity, and at Urban Outfitters. In internet culture journalism, it might mean a TikTok here, a tweet there, plus an Instagram post you had to search for.

I’m not sure how well the rule of three still holds up for writing stories that actually capture meaningful shifts in culture and technology. You can look up virtually any string of words on TikTok and find three or more examples to retrofit into a trend story.

When I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Instagram meme pages this past fall (I’ll publish a version here eventually), I bumped up against the intellectual and creative limits that I think journalism training can produce. I felt myself thinking in terms of trends—driven by a desire to “find the story”—rather than contextualized, meticulous analysis.

While there’s certainly overlap between journalistic and academic studies, I think the former’s urge to fit everything into a cohesive narrative package (even when you have to shove the pieces into the puzzle) is one that makes a lot of academics run away screaming. At the same time, while journalists bristle (often rightfully so) at the granularity, formality, and lack of accessibility of academic writing, our work could benefit from borrowing their methods: meticulous analysis, an emphasis on context, and positionality.

Academic writing emphasizes acknowledging your standpoint—including your discipline, methodology, location, intellectual training, gender, sexuality, and race—all of which can shape your perspective. This obviously runs counter to most basic journalism training, which emphasizes keeping yourself out of the story.

A ton of trend reporting would benefit from this contextualization—like an acknowledgment that a new trend is limited to a specific place or social group, rather than painting with the broad brushstroke of “literally everyone.”

Another example: many headlines declare that Instagram, TikTok, or social media as a whole is “dead.” But is it really? Or are we just using it in different ways, especially as the internet grows more fractured and individual communities take on lives of their own, bounded by the platforms they live on?

Obviously, this kind of analysis requires those of us embedded in the New York media scene to admit we’re not the center of the universe or the internet—that a few people with 50,000 Instagram followers don’t warrant the label of “everyone.”

A greater effort to contextualize trends, rather than limiting a story’s impact, will make it more transparent and ultimately more interesting.

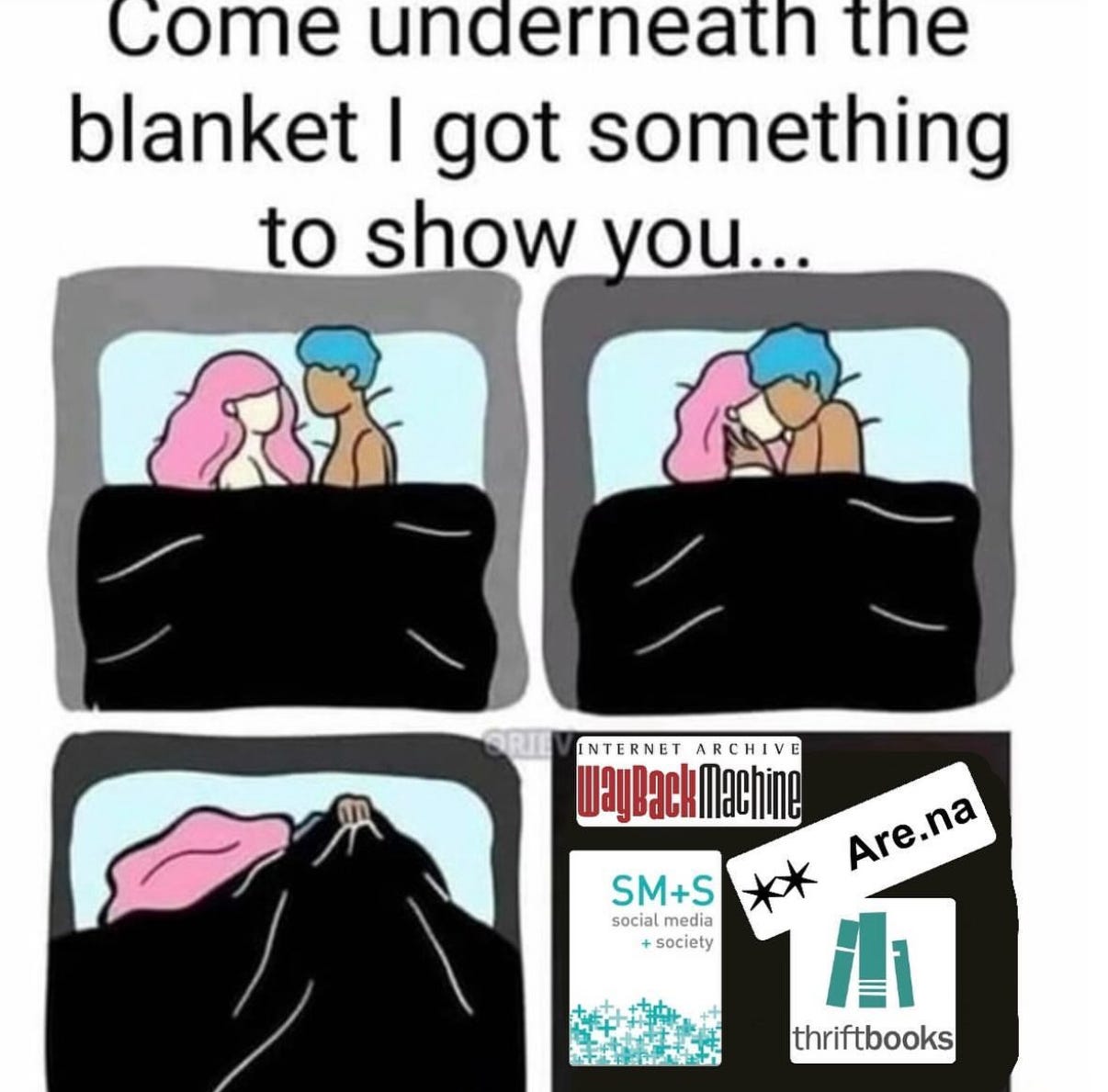

Niche internet corners

The Voros Twins keep raising the bar for posters everywhere.

Memes of the day (follow my Instagram for more)

That focus on the what is trending now question that so dominates the media landscape today does a really effective job I think of fueling our propensity for distraction. Shallow, bordering on superficial. The need to sum stuff up in just a few words or phrases. A blanket of blinkisting.