'The Emergency Was Curiosity': Christie George on attention, creative practice, and useless projects

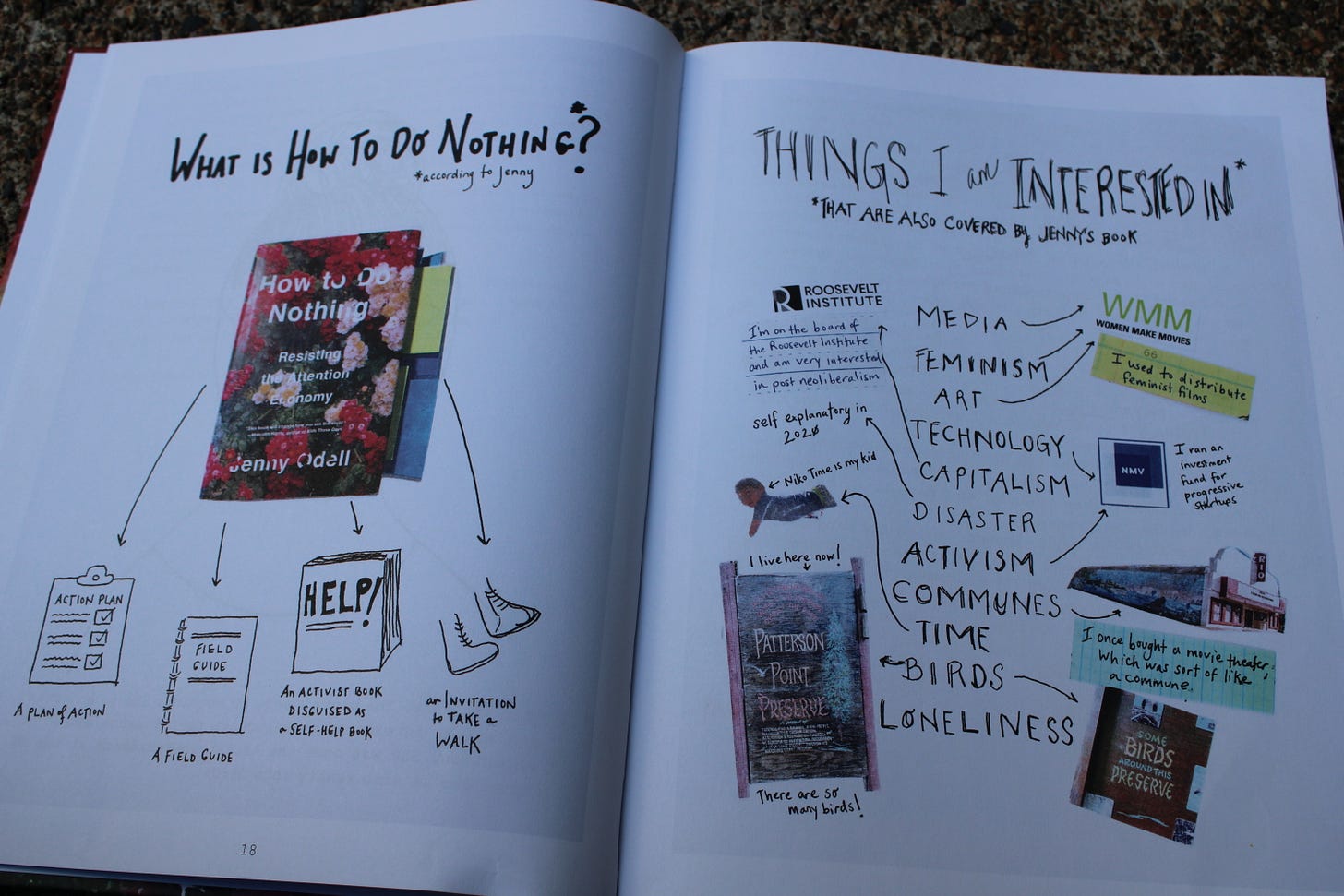

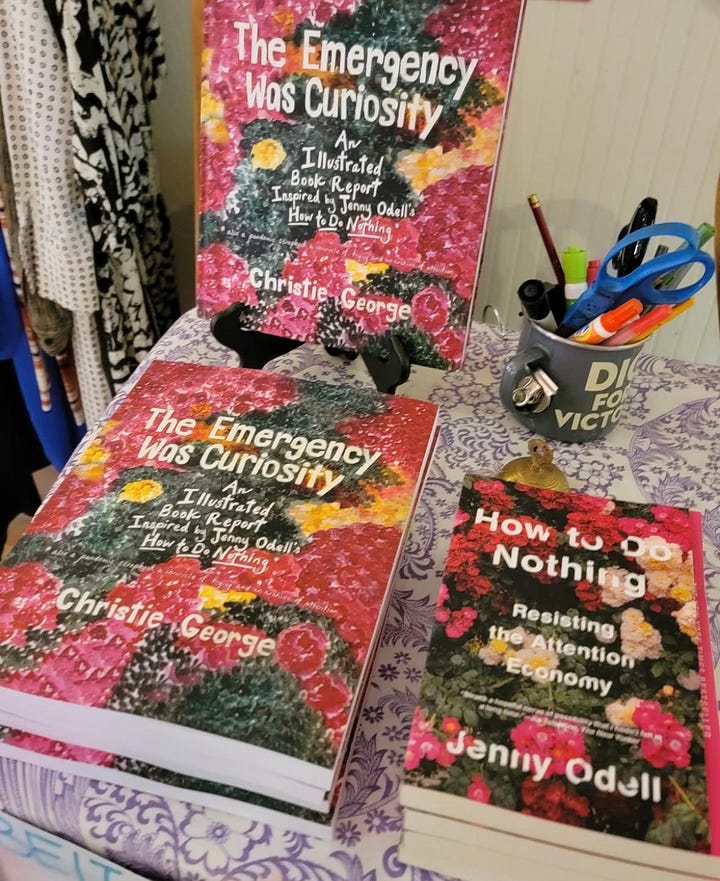

George wrote an "illustrated book report" inspired by Jenny Odell's 2019 book "How to Do Nothing."

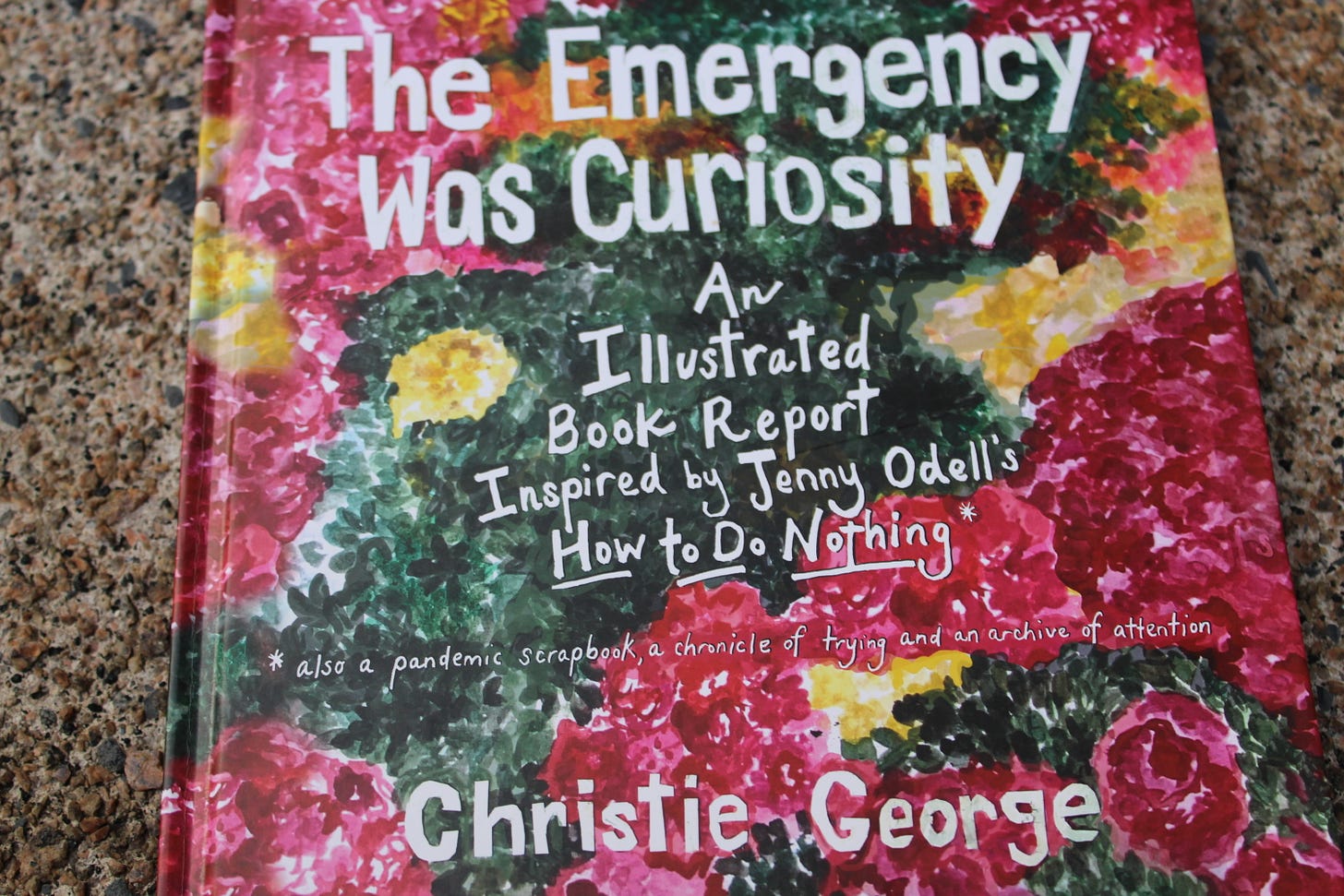

Last month, I went to the Strother School of Radical Attention’s space in Brooklyn for the New York launch of “The Emergency Was Curiosity: An Illustrated Book Report Inspired by Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing” by Christie George.

We sat around a table sipping wine and passing around clementines while George spoke about the book in conversation with Felicia Wong of the Roosevelt Institute. I usually take frantic notes and photos at events I plan to write about, but in the spirit of the space, I left my phone in my bag.

“The Emergency Was Curiosity” defies easy categorization. George began the project as a “book report” on Jenny Odell’s “How to Do Nothing,” released in 2019. It quickly became more than that: “also a pandemic scrapbook, a chronicle of trying, and an archive of attention.”

I spoke with George about the process of making the book and the community that has formed around it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You can find Christie George at christiemgeorge.com. Her write-up of the project, subtitled “In Defense of Useless Projects,” can be found here. Her Substack is Practice Practice.

PHONE TIME: Can you start by sharing your background and how you got the idea for the project?

CHRISTIE GEORGE: My background is in investing, politics, technology, and media—nothing to do with books. I’m just an avid reader and read Jenny’s book, ”How to Do Nothing,” when it came out in 2019. I was on parental leave with my second kid. When you’re trying to take care of a new baby, you’re doing everything, but there’s also a lot of doing nothing.

The book felt very relevant, even though it was about an entirely different thing. I loved it so much I wanted other people to read it.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I found myself remembering pieces of the book. I realized how relevant it was to that specific moment, even though it had been written the year before. I started just taking notes on it. I’m a very fast reader with very little retention, so writing down passages is a way for me to slow down.

I’d also given the book to a bunch of people who talked about its ideas all the time but hadn’t read it. With one person in particular, I thought, “Maybe I could make a little CliffsNotes thing that I could give to him.”

The first version was six pages—a one-page summary for each chapter. I just found that wasn’t enough. I had so much to say about the things I was copying down. I just kept going with it, without any real sense of what it would be in the end. The act of writing by hand, I found very meditative.

PHONE TIME: Getting into your process, when did it go from a kind of CliffsNotes to this bigger project that you could imagine other people reading?

GEORGE: There are probably three points.

I originally thought this would be a summer 2020 project. I was on a sabbatical from a job I had left after 10 years. In August, a friend of friends sent out an email saying she wanted to get together with other creative people. She had her own writing projects she was having trouble finishing and thought it might be helpful to do it in a group of people. That group gave such generative feedback. That was one moment of realizing, “Oh, maybe this can be for other people.”

The second was that I showed a version—probably 50 pages long at this point—to a friend of mine who’s an editor. He was like, “It’s fine, but this seems like you’re trying to tell a different story than a summary of Jenny’s book.” I wasn’t sure I was going to take his advice because I thought the project was done. But I knew he was right. I didn’t quite redo the whole thing, but I reorganized the whole thing.

The third moment was finally when that was finished—at that point I had like 200 pages. I sent it to four very, very close friends. One of those people was ill, couldn’t read it, and asked if she could send it to a friend. I felt bad saying no, and so I just said yes, kind of like, “Oh, God.” There’s nothing super vulnerable, but it is very personal.

That person—who I had never met—was basically the single most comprehending and attentive reader of the entire project and understood so much of why I was doing it. That was a question I had kept asking myself the entire time. She wrote me a 17-page book report about my book report.

I think each of those three moments propelled some version of like, “Okay, let me make this different.”

PHONE TIME: I think that’s such a cool thing to do—to just say, “I’m gonna keep that in because it makes sense to me.” I know at the SoRA talk you spoke about the difficulties in turning this into a bound book because there isn’t really a system for that unless you’re already in the publishing world. Once you realized, “Okay, I do want to put this out into the world,” how did you go about doing that?

GEORGE: The first stage was just 200 physical pages. I needed to figure out how to digitize them. Some were hand-drawn, but some were printouts from a Google Doc. The pages were oversized, so they didn’t fit in a standard scanner.

Eventually, I decided, “I’ve put all of this time into this, maybe I just need to hire someone to digitize the book.” I really wanted it to be a reflection of this time, and I wanted the bad drawings to be kept in. I did eventually find someone that was a friend of a friend of a friend. It’s an oversized book, it’s hardcover, and it’s full color, and I wasn’t willing to do anything that wasn’t that.

Printing a book is actually really expensive, so we had to figure that out too. Probably the biggest difficulty was actually getting people to tell me how much money I should expect to spend. It’s really hard to get people to be honest about money. I think if I had realized that my book was more like a zine or an art book sooner, it would have been a lot easier to get that information. I found zine people to be much more open. They’re just much closer to the means of production, because they’re doing it themselves.

PHONE TIME: Can you talk a little bit about the exhibition?

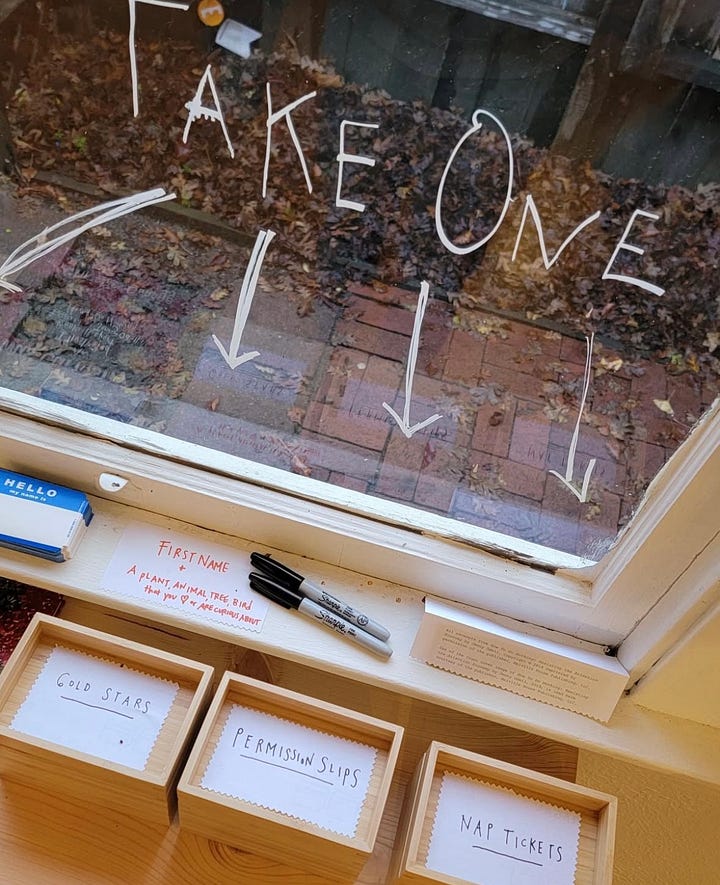

GEORGE: Originally—given that I wasn’t going to print the book—I was trying to figure out how I could share it with people.

I thought maybe I could have the box in a room and people could make appointments. They could read the book during their one or two hours, or just use the time to do whatever they wanted. But that also felt a little pretentious. One book in a room—the vibes of that did not feel like the vibes of our small country town.

A local gallery of mine was having an open call, so I submitted an idea for an exhibition.

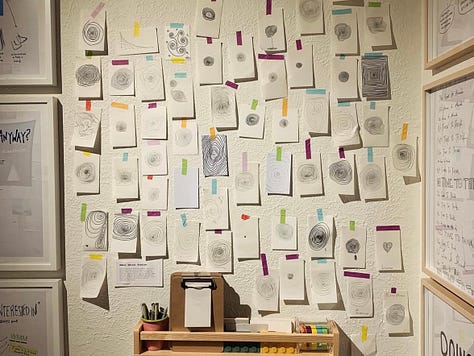

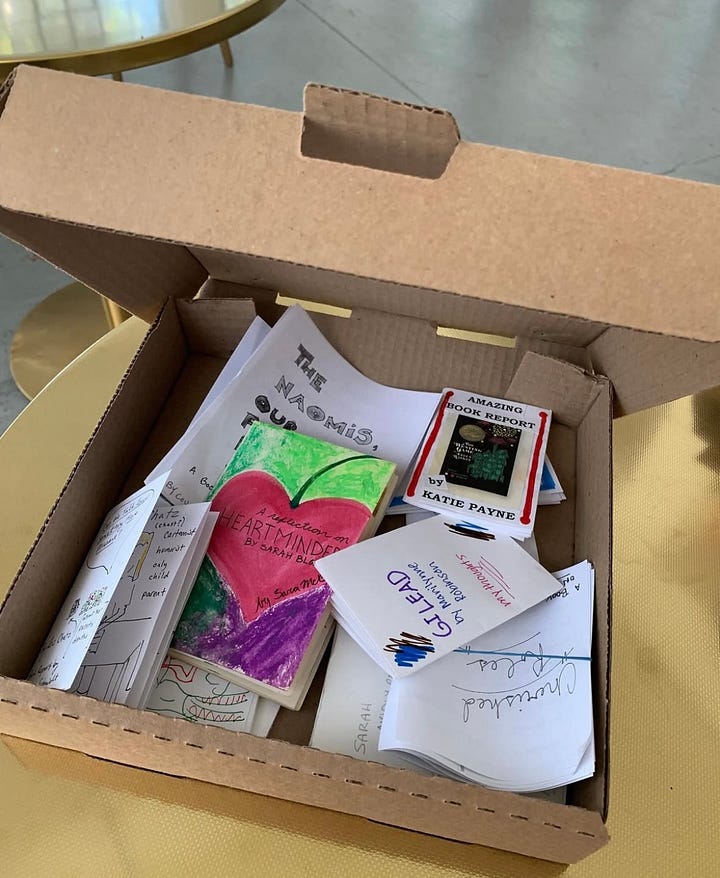

I put the entire book on a wall. It was incredibly tedious. I blew up some of the more relevant pages. All of the books that I read as a result of that one, I put into a little library with a chair so that people could either read or rest.

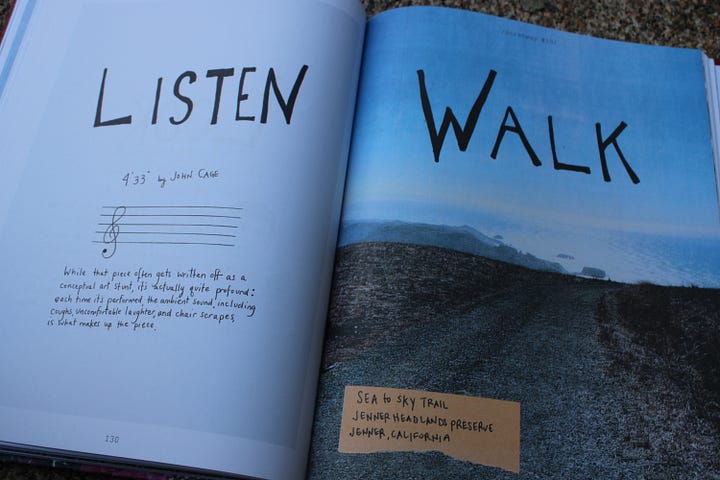

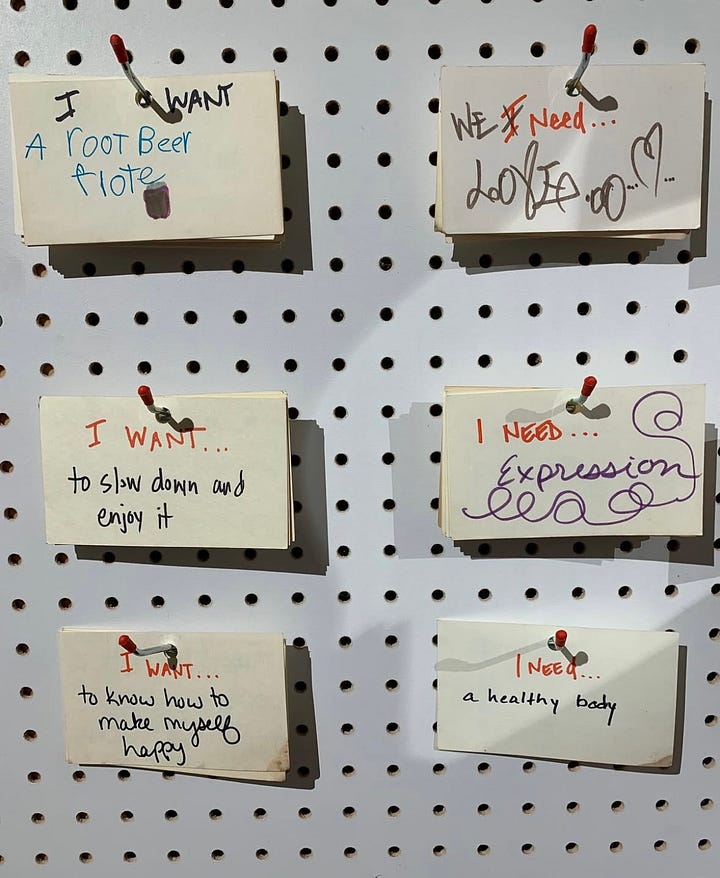

I came up with and borrowed a number of easy exercises around attention. Making a spiral so that the lines are as close together as possible without touching—that’s an exercise that comes from the artist Lynda Barry. There’s another exercise that sometimes people do in art school called blind contour drawing. You either look at another person or yourself with a mirror set up. You set a timer for a minute and draw what you see without picking up the pen and without looking down at the paper. The drawings are ridiculous and hilarious and never good—and that’s sort of the point.

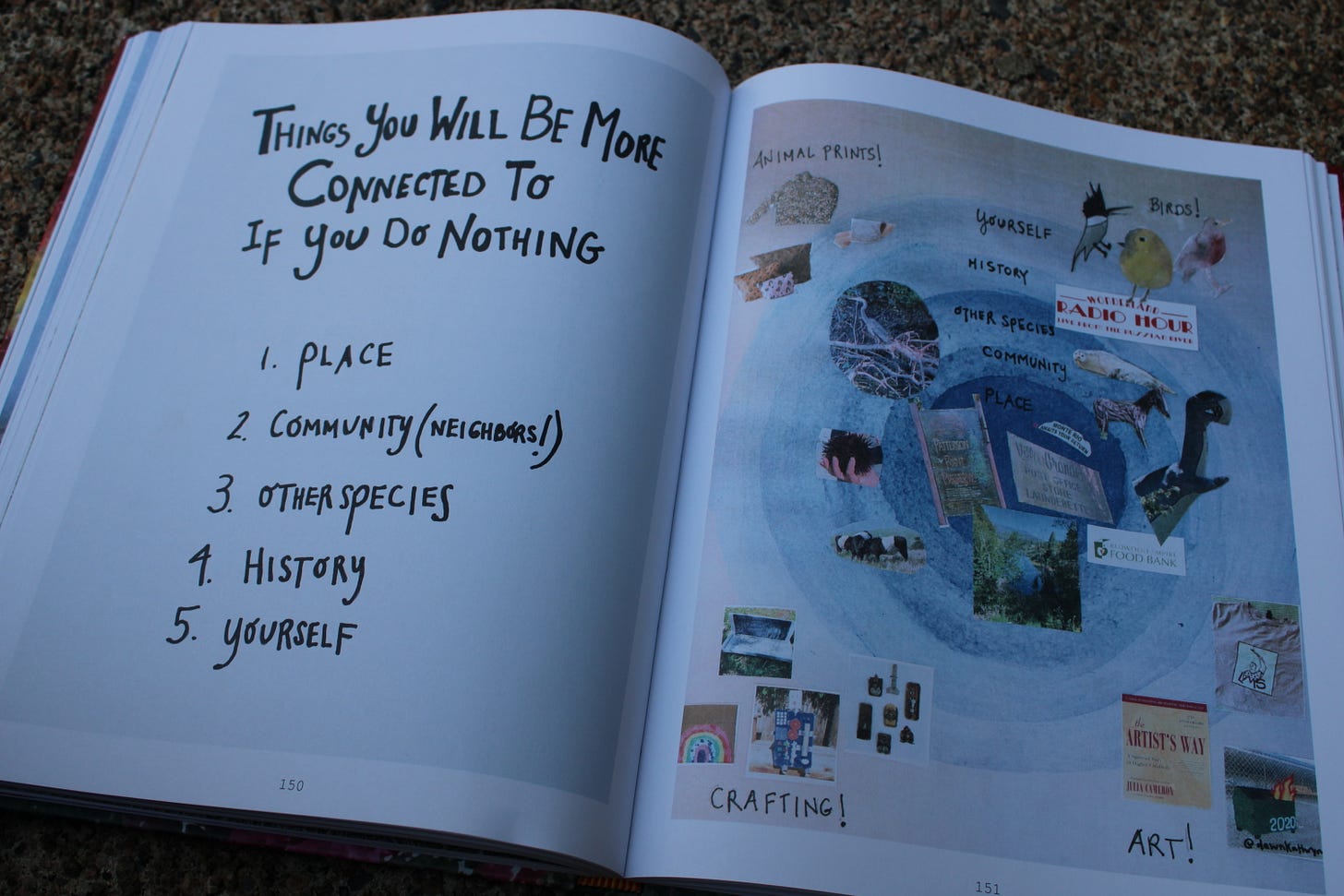

There were a couple of other things as well. The idea was to make it accessible. I think the conversation around attention tends to be very cerebral, very academic, pretty inaccessible, even though it’s an issue for almost anyone.

PHONE TIME: That makes total sense. As someone who feels shame about a lack of attention, I appreciated that SoRA is like, “Everyone has their own ways of cultivating attention and having a creative attention practice.”

GEORGE: I think so many people feel very similarly. So much of the advice around attention, I find maybe necessary but not sufficient. It’s not just “be on your phone less” or something. I both think that’s true, and we need lots of different examples of what we should be doing instead. And it’s not that easy.

Now that I’ve started sharing the project, this is a continuous struggle for me. I’m trying some things, and some of them are dumb, and some of them work. I think trying alongside other people is much easier, more gratifying, more fun, and also more effective than being shamed for what we’re doing or not doing.

PHONE TIME: I know you said that you had seen this as a draft that goes on forever. Are you still thinking about it in that way?

GEORGE: I’m still thinking of it in that way in terms of wanting to be in relationships with people. I’m trying to figure out the way to keep the project going, to continue that. Now that I know how to print things, it’s about the book, but much more about the collaboration with people.

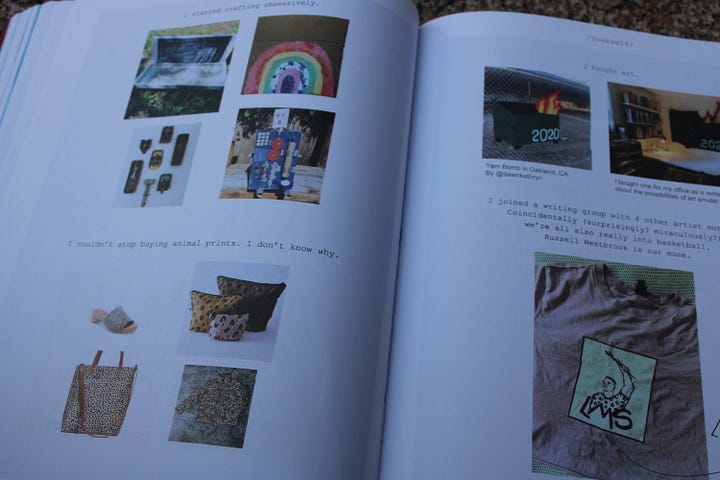

There are so many projects that have come out of the book report that I’m interested in: archives of attention, tons of issues related to midlife, scrapbooking in general. I really want to create a template around personal annual reports. Kind of like the annual reports that come out of companies, but with what you want to remember from your year—something less performative than holiday cards. It may not have an audience. It’s just for you.

PHONE TIME: You talked about the “defense of useless projects.” That’s really interesting to me because I think this ended up having a use for people after all.

GEORGE: It’s not that it’s for everyone. But every time that it finds a person who it speaks to, the interaction is so beyond any other experience I have.

The only way to have gotten here was to have had no attachment to the outcome to begin with—to be making something only for myself and that had no point. I think there’s plenty of utility for things that have a point. Like have a market and all that.

But if I had been worried about whether there was a market for this thing, there’s no way I would have made it.

You can find Christie George at christiemgeorge.com. Her write-up of the project, subtitled “In Defense of Useless Projects,” can be found here. Her Substack is Practice Practice.

Really nice piece. Brings to mind my favorite Shel Silverstein poem…

"Nothing to do?"

Nothing to do? Nothing to do?

Put some mustard in your shoe,

Fill your pockets full of soot,

Drive a nail into your foot,

Put some sugar in your hair,

Place your toys upon the stair,

Smear some jelly on the latch,

Eat some mud and strike a match,

Draw a picture on the wall,

Roll some marbles down the hall,

Pour some ink in Daddy's cap---

Now go upstairs and take a nap.

by Shel Silverstein