Making games that disappear

Game designer droqen on the evolution of his work, droqevers, and newest game "The End of Gameplay."

In today’s issue of PHONE TIME: I spoke with game designer droqen about his expiring games, called “droqevers,” how people have reacted to them, and the evolution of his work.

A couple of weeks ago, I spoke with droqen, also known as Alexander Martin. droqen is a game designer who has made hundreds of games, including “Starseed Pilgrim,” released on Steam in 2013. In WIRED, Ryan Rigney summed up “Starseed Pilgrim” as “an interactive riddle, an almost Joycean puzzle.”

“You will discover how and why the world sometimes flips into an alternate dimension. After planting numerous colored seeds, you will develop strategies to navigate carefully. Every piece in the puzzle has a specific meaning, and only through thoughtful play will you decode it,” Rigney wrote.

I’m not an expert on games, although I’ve reported a bit on them before. I dug into the world of indie games while researching droqen and his work, but I’ll say up front that this isn’t a complete picture of his output, which is quite prolific. I’d also recommend this episode of the Everybody’s Talking at Once Podcast, in which droqen elaborates on his approach to making games and his new game, “The End of Gameplay.”

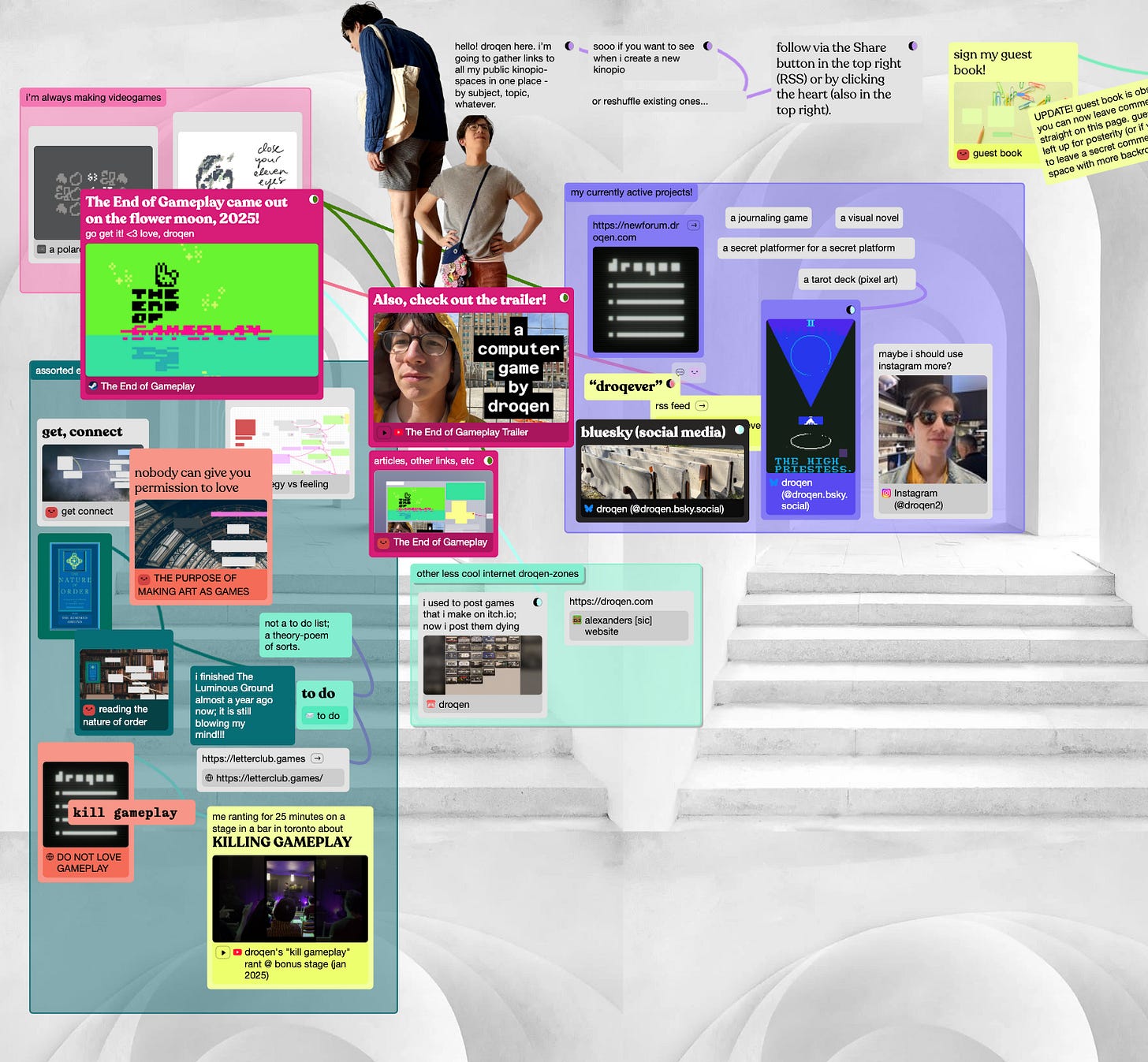

You can find droqen at his website, Kinopio, Bluesky, YouTube, and X. “The End of Gameplay” is available on Steam and itch.io.

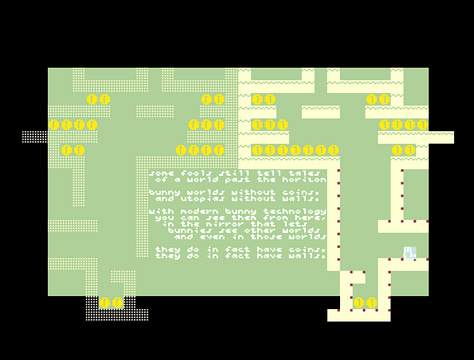

We talked mostly about “droqevers,” games droqen has made that expire. “i don’t like having my games up forever, so i made them expire after some random # of days! i’ll post another game somewhere on the internet soon and it will be better!” he describes on the droqever website.

In October 2021, droqen had made a game every day as part of “droqtober”—modeled after Inktober, a drawing challenge where participants create an ink drawing every day for 31 days.

These games are now compiled in “31 unmarked games,” where, as the description reads, “you'll receive 31 unmarked cassette tapes in a little digital mailbox. Some contain short experiences: playable practical jokes, maybe. Some are little finishable arcade games or platformers. A few of the thirty-one are confounding puzzle-boxes that might even last you an hour or two each.”

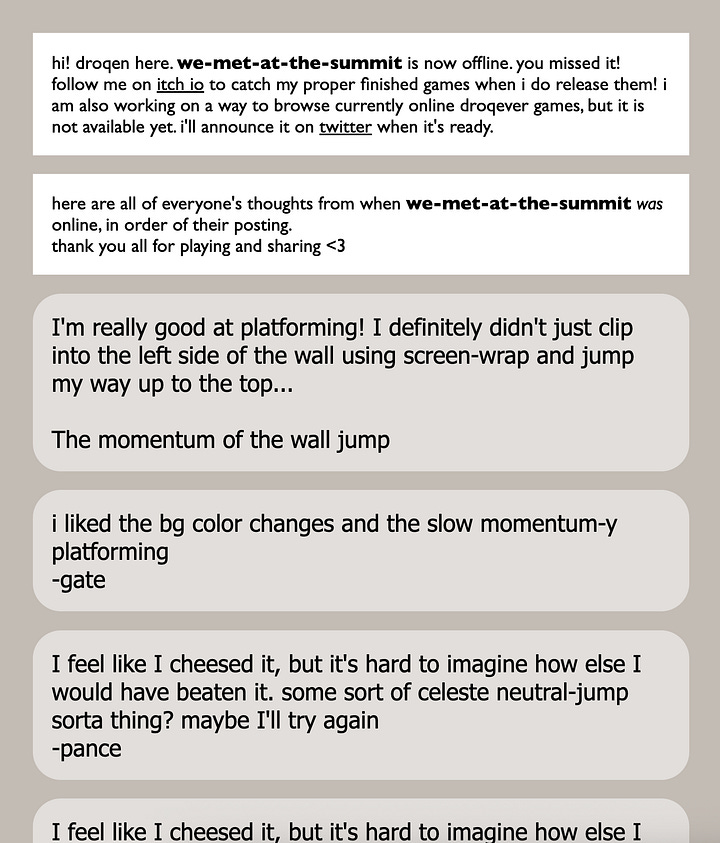

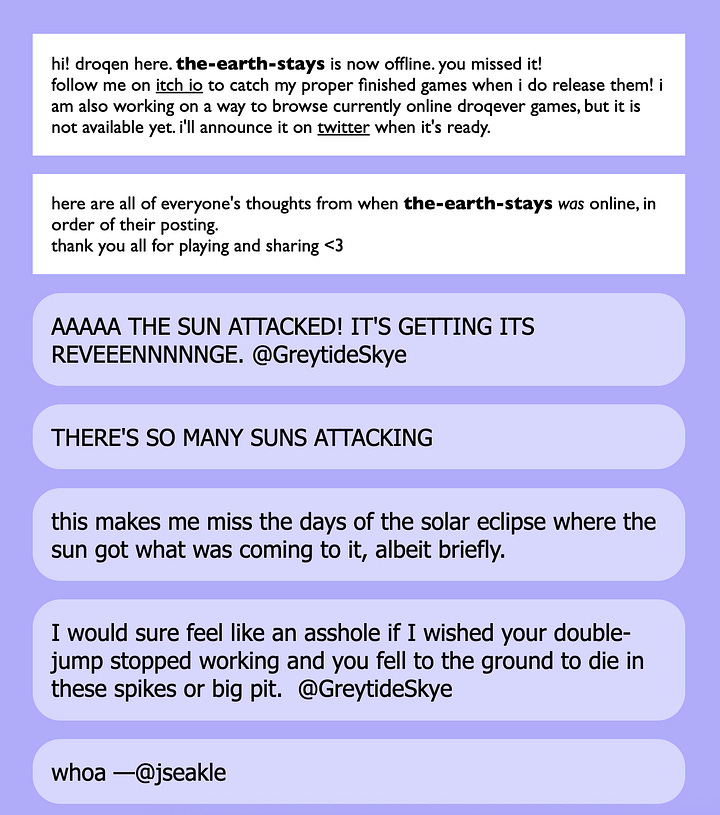

While droqen had enjoyed putting up new games each day, having a calendar full of 31 games felt like too much up at once. So he began to make them disappear after some time. When a game goes offline, all the comments left on it remain visible, in the order they were posted.

droqen noted people’s reactions to the disappearing nature of the droqevers, which sometimes included suspicion.

“Some people are like ‘I could never do that,’” he said. “People treat their games and releasing them really seriously, so I think they can’t imagine throwing it away.” Others have enjoyed that the “games live on in memory in this fuzzy, idealistic way.” With droqen’s permission, videos of the droqevers have also been uploaded to YouTube by the account Username404.

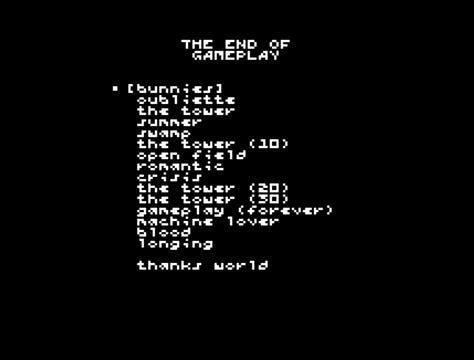

“The End of Gameplay” is the title of droqen’s newest game. I’ve embedded the trailer below. In his “untitled kill gameplay video,” droqen also connects the process of making games to art therapy.

“This idea that making games is something that you can do because it’s good for you. It gives you a sense of purpose and meaning—and not because it’s a job or it’s going to make you a bunch of money or because, I don’t know, a museum is going to like it—but because the actual act of making something…can be very meaningful to a person. It can do so much for you,” he says in the video.

In the video, he also reflects on the legacy of “Starseed Pilgrim” and how his thinking about games has evolved since.

“My most distant hope is that if ‘The End of Gameplay’ can gather even remotely close to the amount of attention that ‘Starseed Pilgrim’ got, I would want it to be about this function that games serve for people,” he says. “For some people—not everyone—games can be a genuinely expressive art form.”

“The End of Gameplay” feels like a culmination of the droqevers, droqen told me. He said that making the droqevers felt kind of like dating, whereas “The End of Gameplay” is more like a “long-term relationship with a longer and more serious game I made.”

While droqen said he loves “the feeling of not rushing into releasing something,” he also emphasized the value in sketching and experimenting. Looking ahead, he plans to make work about more “weird emotionally vulnerable stuff” as a tool for processing things.

“I think if I do find another way to deal with the future and the past that’s better than games, I will absolutely do those things. But games have been with me for so long that I think if I switched to another medium I’d miss it all too much,” he said. “Like, I can write a song, but I’d miss doing level design, bumping into walls, making little mazes.”

Learn more about droqen’s work:

“‘The End of Gameplay’ is an anthology. My best desperate attempt to explain, or explore, or understand the true meaning of ‘kill gameplay,’” reads its description. Find “The End of Gameplay” on Steam and itch.io.

“Who Could Want Gameplay? with Alexander Clair Tseu Martin (a.k.a. droqen)”—Everybody’s Talking at Once Podcast, Episode 184

“droqen's ‘kill gameplay’ rant @ bonus stage (jan 2025)”—droqen via YouTube

“a HAIKU games manifesto” by droqen