Looking back at the Kardashian-Jenner apps

Plus, an update on the AI Barbie box "starter pack" trend and some tech happenings around New York City.

This week, I was reminded of a relic from an earlier era of social media: the Kardashian-Jenner apps. Launched in 2015, the apps offered behind-the-scenes content from each sister—covering beauty, fashion, lifestyle, and daily routines—for $2.99 a month.

By late 2018, Kourtney Kardashian, Kim Kardashian, Khloé Kardashian, and Kylie Jenner had each posted statements announcing the impending shutdown of their respective apps, which also had corresponding websites. Kendall Jenner had already stopped updating hers.

In a 2018 article for Vox, Kaitlyn Tiffany wrote about the end of the celebrity app boom. The latter half of the decade had seen apps from celebrities like Taylor Swift, Kristin Cavallari, and Jeremy Renner. Tiffany argued that because these celebrities had built their brands around constant access to their lives, it was difficult to now suddenly make people pay for that same content. The individual apps’ lack of rigorous moderation systems also proved an issue.

While the Kardashian apps ultimately failed to pan out, convincing people to pay for extra content and perks—whether it be bonus podcast episodes, access to newsletters, reading lists, invites to subscriber-only parties—is the business of countless creators and influencers today. Notably, these efforts are largely housed on existing digital platforms like Patreon and Substack, rather than standalone apps or websites.

Unlike the Kardashians, many creators today can provide (or at least give the appearance of) relatability and authenticity. Features like subscriber-only group chats or comment threads enable two-way conversation and community building, as opposed to a one-directional stream of content from exorbitantly privileged celebrities.

The apps were not the Kardashians’ first try at building out separate spaces to share updates with their audiences, as they had previously shared personal and professional updates as well as photos through blogs.

Celebrities today have not abandoned the idea of monetizing exclusive access—think Cameo or the Spotify features allowing artists to send out Wrapped videos or other goodies to fans.

An update on the AI Barbie Box “starter pack” trend

When I wrote earlier this month about the AI Barbie box trend—also known as the “starter pack trend”—brands, influencers, and creators were just beginning to post AI-generated doll versions of themselves, complete with accessories. I wanted to add some concluding thoughts as the trend fades out.

I was surprised by how many brands jumped in. I attribute the format’s customizability to various branded products—more so than the Studio Ghibli trend. While it is pretty easy to tell that many of the iterations were AI-generated, as AI imagery improves (and becomes less Shrimp Jesus-like), brands are going to have to make big decisions about if and how they should be using the technology.

In this case, even the participating brands seemed a bit reluctant or bashful, with captions like “we had to.” In response to negative comments, brands emphasized the role of design and creative teams in the making process, while sidestepping whether they had used AI.

When one commenter asked ceramics and home decor company Mackenzie-Childs to support actual artists by not using AI, the brand responded “Our graphic designers/Creative team actually put this together for us!” (In another reply, they acknowledged using AI).

On Graza’s version, the brand responded to a concern about AI with, “Don’t worry our designer put her own spin on it!”

Girl Scouts used the caption, “At Girl Scouts, we believe in teaching girls digital literacy and how to navigate the ever changing digital world. This image was made by an illustrator using the AI trend as inspiration.” The post received mostly negative comments.

NARS Cosmetics responded to criticism, saying “We were inspired by the AI trend; our wonderful creative team perfected the final result with Photoshop and real NARS images.”

Here’s a sampling of brands that participated, based on a scroll through their Instagram feeds: LoveShackFancy, PopUp Bagels, Florence by Mills Coffee, e.l.f. Cosmetics, Clinique, Supergoop, NYX Cosmetics, Macy’s, KitKat, Sephora, MAC Cosmetics, Victoria’s Secret PINK, Summer’s Eve— and not a brand, but Hunter College.

And some that didn’t: Fishwife, Brightland, Moon Juice, Olipop, Ghia, Apollo Bagels, Chamberlain Coffee, Kin Euphorics, Summer Fridays, Glossier, Dunkin’, Sephora, The Ordinary, Benefit Cosmetics, Sprinkles Cupcakes, Duolingo, Wildflower Cases, 818 Tequila, Olfactory NYC.

My non-methodical assessment: the trend was especially appealing to beauty brands and creators. I saw countless estheticians make their own versions, as well as big names like MAC and Sephora. It’s a trend that works particularly well for this industry, allowing them to incorporate many smaller makeup, beauty, and other consumer products. Brands that frequently joined in on memes and trends were likely to participate, while those with more curated, editorial feeds—especially food brands—held off.

The broader starter pack meme format lends itself especially well to brand use, allowing products or services to be easily arranged into visually striking collages. This AI trend was a continuation of that style, while also adding an anthropomorphizing element.

The trend also kicked off an interesting interplay between human-created (obviously a term with embedded assumptions) and AI-generated content—a back-and-forth I think we’ll continue to see. Artists (and some brands, such as Farmacy Beauty) responded with illustrated versions of their own, often including labels like “Real Human Artist.” This also happened with the Studio Ghibli trend—as people started sharing AI-generated images, many responded with their own illustrated works.

Tech around town

The Museum of the Moving Image is hosting a programming series called “Reframe: Experimental Technology and the Moving Image.”

“Showcasing the work of two artists, Libby Heaney and Laura Splan, this program aims to confront the growing gap between widespread use of digital tools and a genuine literacy and understanding of it,” describes the museum’s website.

On April 11, I went to the first of the two performances: “Eat My Multiverse” by artist and quantum physicist Libby Heaney. The audiovisual performance was multisensory, poetic, and quite visceral.

Following the performance was a discussion between Heaney and Regina Harsanyi, the museum’s associate curator of media arts. They discussed the race among governments and corporations to develop quantum technology, the global inequities in access to those tools, the limitations artists face in shaping technological futures, and the rise of “quantum woo,” a term for pseudoscientific adaptations of quantum ideas, often seen within the wellness industry.

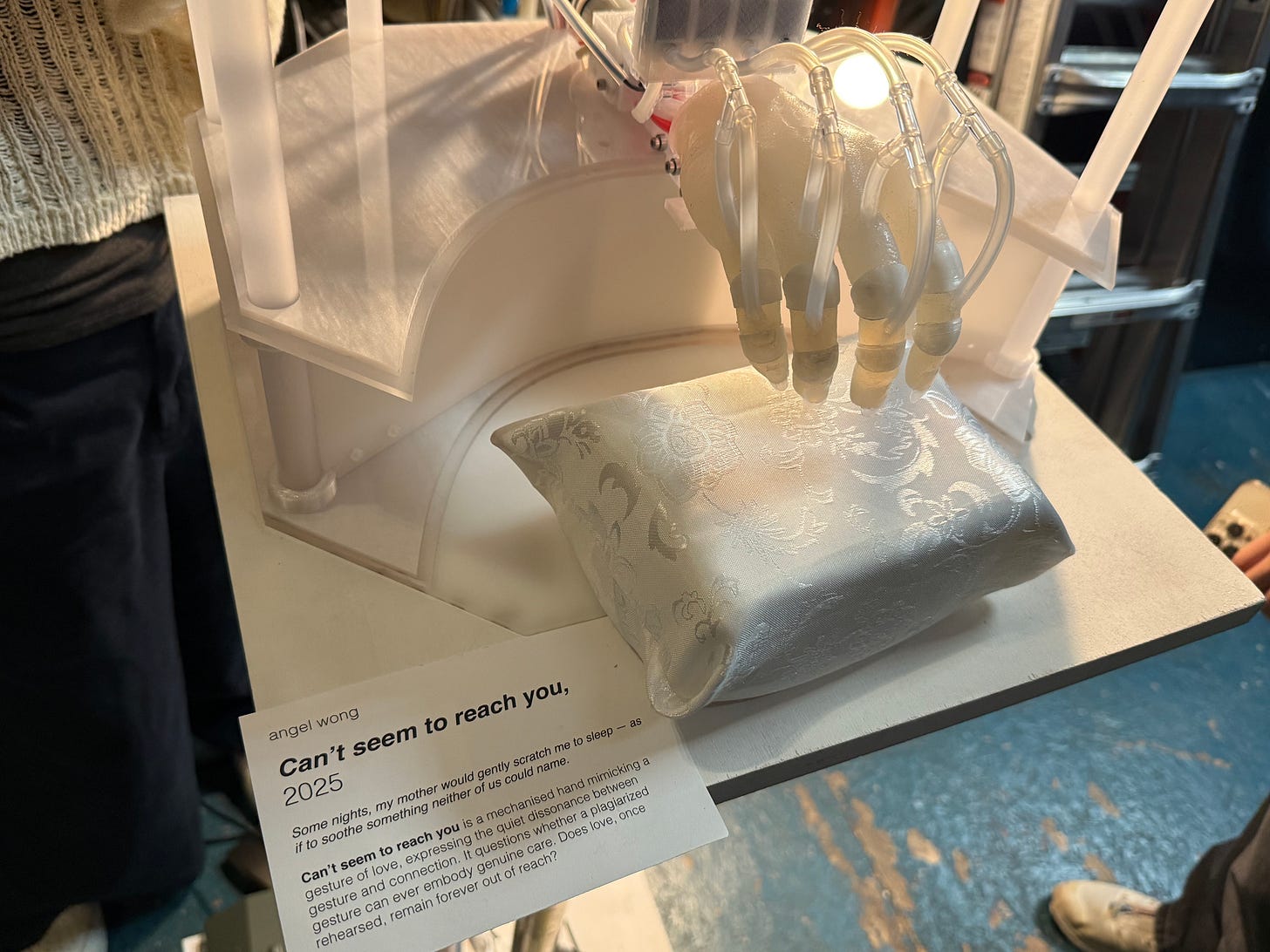

NYC Resistor hosted “To Be Continued,” a show of thesis projects from New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program on April 12, featuring works from 18 students in the program. The works explored themes and topics like online and offline connection, crisis, news, and memory.

You can find archives of past ITP projects from 2024, 2023, 2022, and 2021.

Niche internet corners

Tiramisu is having an online moment. Videos of “tiramisu purses”—transparent glass purses filled with the dessert—went viral in late December and early January, reported Merlyn Miller for Food & Wine. There was the “carimisu” video, featuring tiramisu served from a center console. And the tiramisu drawer. In March, Olivia Craighead declared the Yankees souvenir hat “Finally, the Right Vehicle for a Tiramisu.”

There had been tiramisu trends (I’ll hold off on my state-of-trend-reporting meta-analysis for now) in years past. There was the viral tiramisu latte, the release of tiramisu Oreos, and even “tiramisu hair” (don’t worry, this is just a style of balayage). The dessert has also become meme material, though I don’t think it’s that deep. It feels like the latest installment of memes revolving around food objects, including pickles, tinned fish, and Diet Coke.

New York State is embracing memes on Instagram. The account had been posting memes occasionally in 2022 and 2023, ramped up frequency in 2024, and now seems to be going all in.

Memes of the day (follow my Instagram for more)

The New York Times recently put out a story headlined “The Color-Drenched Cult of Le Creuset,” written by Julia Moskin. Last year, I made a meme gently poking fun at the online fandom of Le Creuset, which reminded me a bit of the Stanley Cup obsession. It got more than 60,000 likes and a healthy number of quote tweet dunks. Based on the word “cult” in the Times’ headline, I’m declaring my tweet vindicated.

“It's a lofty goal, but Substack's strategy of bringing online communities offline into the real world is something social startups and creators alike are trying to crack. As young adults navigate loneliness, some creators are filling the gaps for those seeking a sense of deeper connection through longer-form videos, podcasts, and newsletters,” Sydney Bradley wrote for Business Insider in October 2024, reporting on the plethora of readings and other events Substack was organizing.