Inside 'Small Batch,' a farmers market for datasets

Curated and organized by Claire Hentschker, the market showcased data at its most poetic, investigative, and strange.

Two Sundays ago, inside the WSA building in Manhattan’s financial district, visitors browsed a selection of artisanal goods and chatted with vendors. But instead of produce or bread, this farmers market was all about data.

“Small Batch: A Dataset Farmers Market,” curated by Claire Hentschker, featured datasets from more than 40 vendors, both in person and remote. In-person vendors offered zines, prints, and USB drives, along with QR codes linking to their datasets. Remote vendors displayed printouts of dataset descriptions on tables, also paired with QR codes.

Datasets included a map of New York City breakup spots, music libraries from old iPods, poems about surveillance, and images of Museum of Modern Art tote bags spotted on Google Street View.

The market was part of “Another Internet Is Possible,” the second weekend of Rhizome World, a monthlong pop-up in New York City. The weekend focused on “alternative and experimental networks.”

It was the second iteration of Small Batch. The first took place last winter at LARPA, a shared studio space in Bushwick where Hentschker oversees logistics and organizes events. She described the studio as a place for arts, crafts, and activities for people interested in the medium of technology.

LARPA has previously hosted “high concept, low effort” film screenings, including “Avatar: The Way of Water” averaged down to one line of pixels per frame, and a motion-smoothed version of “The Blair Witch Project.”

Hentschker began thinking about organizing a data fair amid the ongoing discourse about artificial intelligence and how it impacts artists.

“This sort of terrible heist [had] happened…at these companies downloading the entire internet and entire portfolios and training all these models on the images that artists are putting out there,” she said. “It’s just so crazy and cruel. And once it happened, it’s also like, you can’t go back.” But Hentschker also noted the difficulty in ignoring AI as a tool and emergent technology.

She described the market as an experiment in valuing data as a material and something that can be exchanged and cultivated. She noted attendees’ interest in a dataset by Sarah Rothberg, an artist and assistant arts professor at New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, which featured point-of-view GoPro footage of her cleaning her apartment.

Hentschker, who has a background in photogrammetry and 3D reconstruction, connected her interests in technology and data to a love of crafts. “I love hoarding craft supplies,” she said. "Like, there’s a pack of 1,000 stickers. I don’t know what I’m going to do with these yet, but I’m going to buy these.”

Hentschker said she hopes to host more events like Small Batch in the future. She described exploring the question, “If my favorite type of interactive website was actually an event, what would [it] look like?”

She also expressed interest in creating a system for anyone to be able to organize data fairs, making it decentralized. “I feel like it’s out of my hands in a good way,” she said.

After the market, I reached out to a few of the vendors about their datasets (interviews conducted via Zoom, Instagram direct message, and email, respectively; edited for clarity and length).

IVAN ZHAO

Dataset Name: “Small Corpus of Gutenberg Poems and Associated Weights”

Description: “This is a small corpus of lines from Project Gutenberg, where I trained a Markov model on all of the parts of speech and the next part of speech it would predict for my blackout poetry generator.”

PHONE TIME: Tell me a bit about how the Gutenberg poem project came together.

IVAN ZHAO: I was really interested in blackout poetry for a period. I write poetry and make internet art and games, and I was really interested in: Is there a way to make this generative? And when you make it generative, what are the ways you can make it “good” or something that can replicate a human?

This was actually before LLMs got really big and mainstream. I made this project back in late 2022, early 2023. I wanted to make more tools on the internet to make poetry and art. The website is essentially this input field where you can generate blackout poems through either a random generation or a “smart generation.”

For smart generation, I had taken this corpus of poems from Project Gutenberg. I took all of the lines of text from this poetry text corpus and ran a Python script that converted every text instance into its corresponding part of speech.

From there, it serves as a Markov model—a probability matrix, where the rows and columns are anything you want them to be. In our case, we care about parts of speech. You can create this probability distribution from every possible part of speech you have, to predict, what the next word should or could be. It’s kind of a more rudimentary version of what large language models are, but something about this feels more fun and generative to me.

PHONE TIME: How long did it take to make?

ZHAO: I think this project took me a weekend or so. It was very much like, “I want to make this random thing.”

PHONE TIME: How do you think about data as an art medium?

ZHAO: There are so many different dimensions to think about this. I think most in terms of personal data and the question of access: Who has access to this data? Where is this data coming from? And what role does it play?

I am really interested in archives, family archives and research, and specifically about image data. What images are we able to pull from the family archive? Where did these images exist, and how do we preserve them? I think there is a lot in being able to use and manipulate images in order to create some new meaning.

There’s different questions around data and data processing and how “usable” something is. And then there’s also this theoretical, technical layer. Where as long as you have the tool that renders and shows it correctly, any given possible data set could be presented in some way.

PHONE TIME: Are there any different directions you see this project going in or things you’re inspired to make?

ZHAO: A half-baked project that I was working on was a different way of composing free verse poetry. I’m really interested in the idea of the line break and indentation. In digital poetics, there are folder structure poems: you title a folder and then there’s a subfolder. You can create these tree diagrams with your recursive folder structures.

But this has existed in poetry as well and is used in older poetry in indentation and line breaks. I was like “How do I programmatically think about this?”

So I was working on a tool that was more of a canvas-based way of writing free verse poetry. I think most document editors that people are using to write poetry—like Google Docs, notes apps, it’s not really meant for that kind of thing. It’s not at that level of granularity. When you look at the history of printing, a lot of poets, some of them started off as printers because they cared a lot about where the actual text was placed on the page. I’m really interested in this idea of how you augment words through a programmatic semblance.

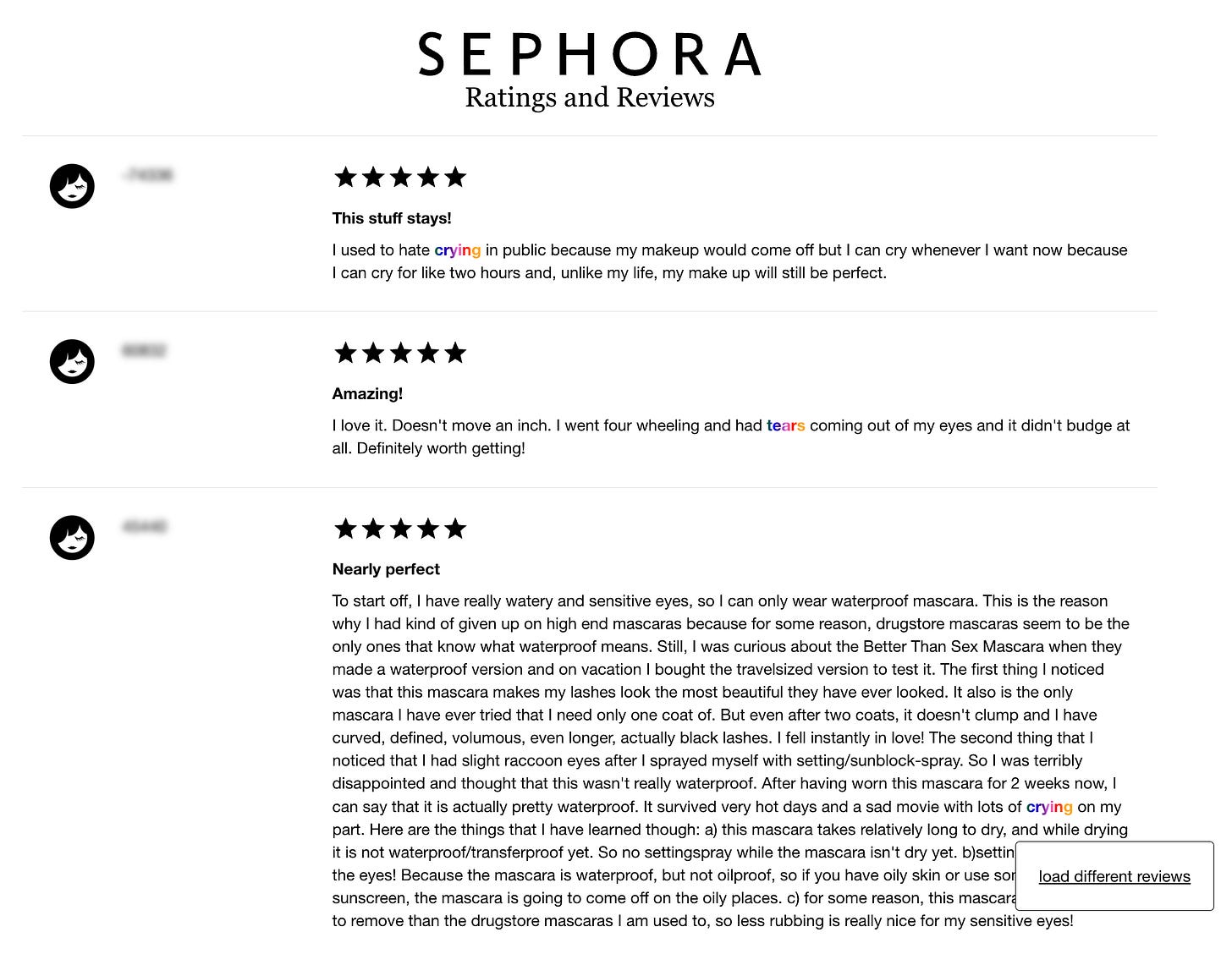

CONNIE YE

Dataset Name: “Sephora Makeup Reviews that Mention Crying”

Description: “The dataset delves into the interplay of resilience and fragility, as reflected in waterproof makeup reviews. This archival piece was extracted artisanally from Sephora.com in 2019.”

PHONE TIME: How did you come up with the idea for the dataset? How long did it take to make?

CONNIE YE: I actually made the dataset almost six years ago in Fall 2019, as part of a class I took in art school with a visiting artist named Everest Pipkin. We were tasked with creating new datasets, and I was thinking about how I had spent a lot of time looking at Sephora reviews for waterproof makeup—many of those reviews were unexpectedly so sincere and poignant!

I don’t exactly remember how long it took to make, but I probably did it in a few hours one night. I had a script that would just read the contents of a Sephora webpage and pull the data into a JSON format, but I didn’t have time to automate it very much. So I’d just find products that looked promising, go to their pages, and run the script in the JavaScript console.

PHONE TIME: Is there any kind of reaction—emotional, intellectual, artistic, otherwise—or response you hope it elicits for people coming across it?

YE: Personally I think the best part of making art is that I get to be surprised by the response to my work. I do hope they can enjoy the little review viewer site if they haven’t seen it already.

My favorite response has been from the data analysis/visualization community—such as from FlowingData, and I recall someone ran sentiment analysis on the dataset, although I can’t find that blog post anymore.

PHONE TIME: How do you think about data as a medium?

YE: As an artistic medium, I wish it was something I spent more time exploring! The meaning of “datascraping” has shifted a bit since I made the dataset in 2019, but Claire [Hentschker]’s Small Batch data farmers market is a huge inspiration for me in how it models the potential for data to be art when farmed in a certain way.

ALEXA ANN BONOMO

Dataset Name: “Flora of the Bible”

Description: “A dataset of all the plants reference in the Bible. Includes their common name, their Latin name, where they are referenced and an image.”

PHONE TIME: How did the inspiration/idea for the project come to you? Are there any ways you hope viewers respond to it (intellectually, creatively, emotionally, spiritually, etc.)?

ALEXA ANN BONOMO: I am always just fascinated by scraping data from beautiful texts and was curious about how plants and animals were talked about in the Bible. I wanted to know what symbolism they may have and what significance they brought. I also had been teaching Hydra in a class so it gave me an opportunity to practice some of the skills and use a 3D scan I made on a site.

PHONE TIME: How did you think about the visuals on the website in conjunction with the dataset?

BONOMO: The visuals are using a bunch of videos that I took with an old handy-cam. I mostly was having fun with layering them and seeing what the effects might do.

PHONE TIME: How do you more broadly think about data as a medium?

BONOMO: I think of data as a collection of information that may hold various levels of meaning. I am inspired by collections of data that may be considered sacred or hold memories that can be viewed in various forms.

PHONE TIME: Any further directions or addendums you could envision the project taking?

BONOMO: This was a very short-term project that took me a day or two. I would want to play more around with the visuals a bit more. I can also see a project forming out of this that could be more narrative with multiple pages and 3D scans.