Daughter Zine has memes, pink aesthetics, and the feminist politics to match

A conversation with founder and editor in chief Grace Anne McKean.

Today’s issue of PHONE TIME is about Daughter Zine, a publication that spans platforms including a Substack blog, an Instagram account, and zines and anthologies available both online and in print. Plus, a reading list covering zines, print, girlhood, and the internet.

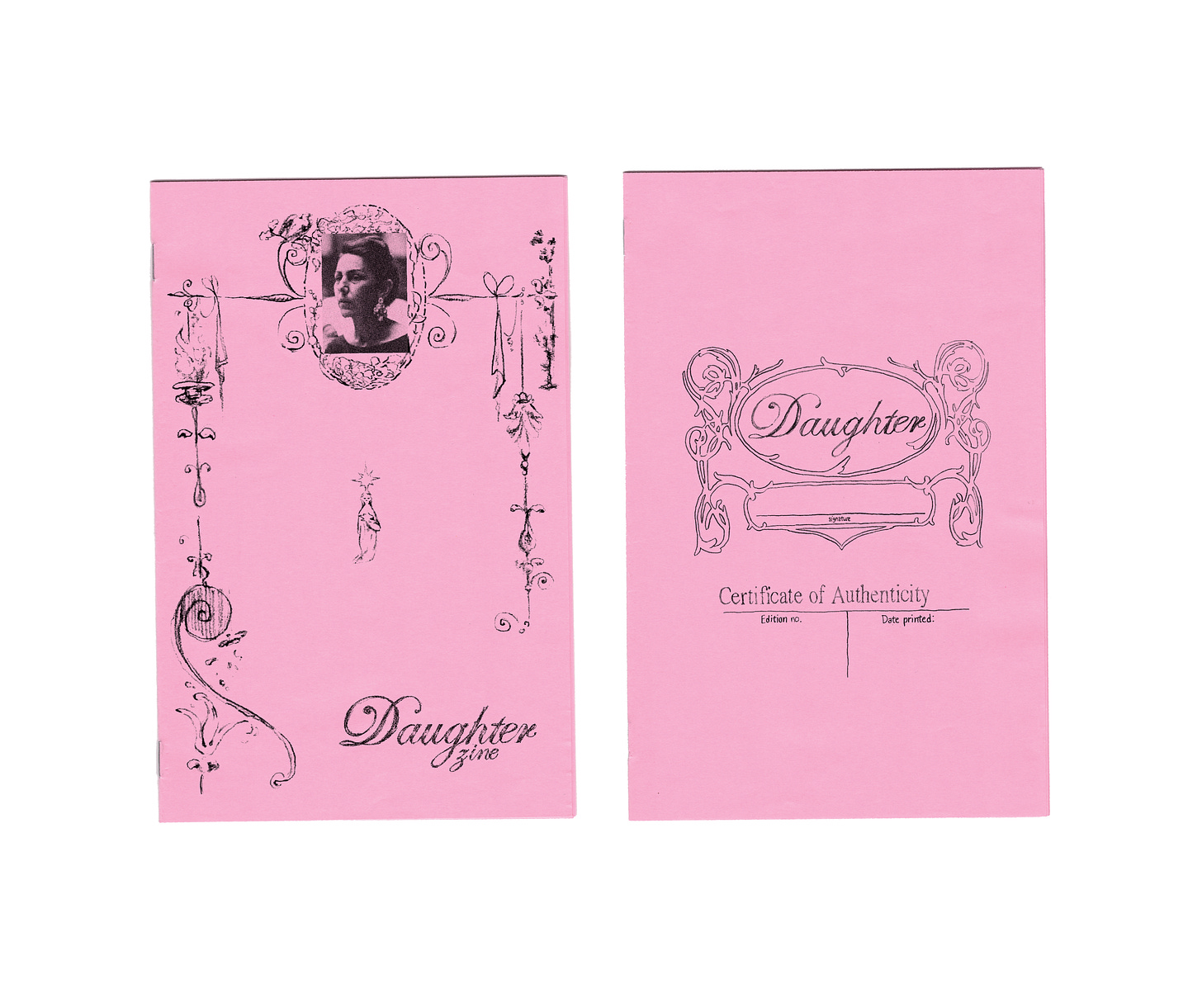

Daughter Zine describes itself as “created by every girl you know & every girl you'll never understand.” I first came across Daughter on Instagram and was quickly drawn to its striking visual presence, consisting of curated images, memes, and scans of illustrations and writing.

To say that “girlhood” has had a bit of an online moment these past few years might be an understatement. Think girlbosses, girl dinners, girl math, hot girl walks, and just about every iteration of a “girl summer” you can imagine. But what many of these trends, and the flood of trend pieces that followed, lack is feminist politics. The kind that’s informed, imaginative, even radical.

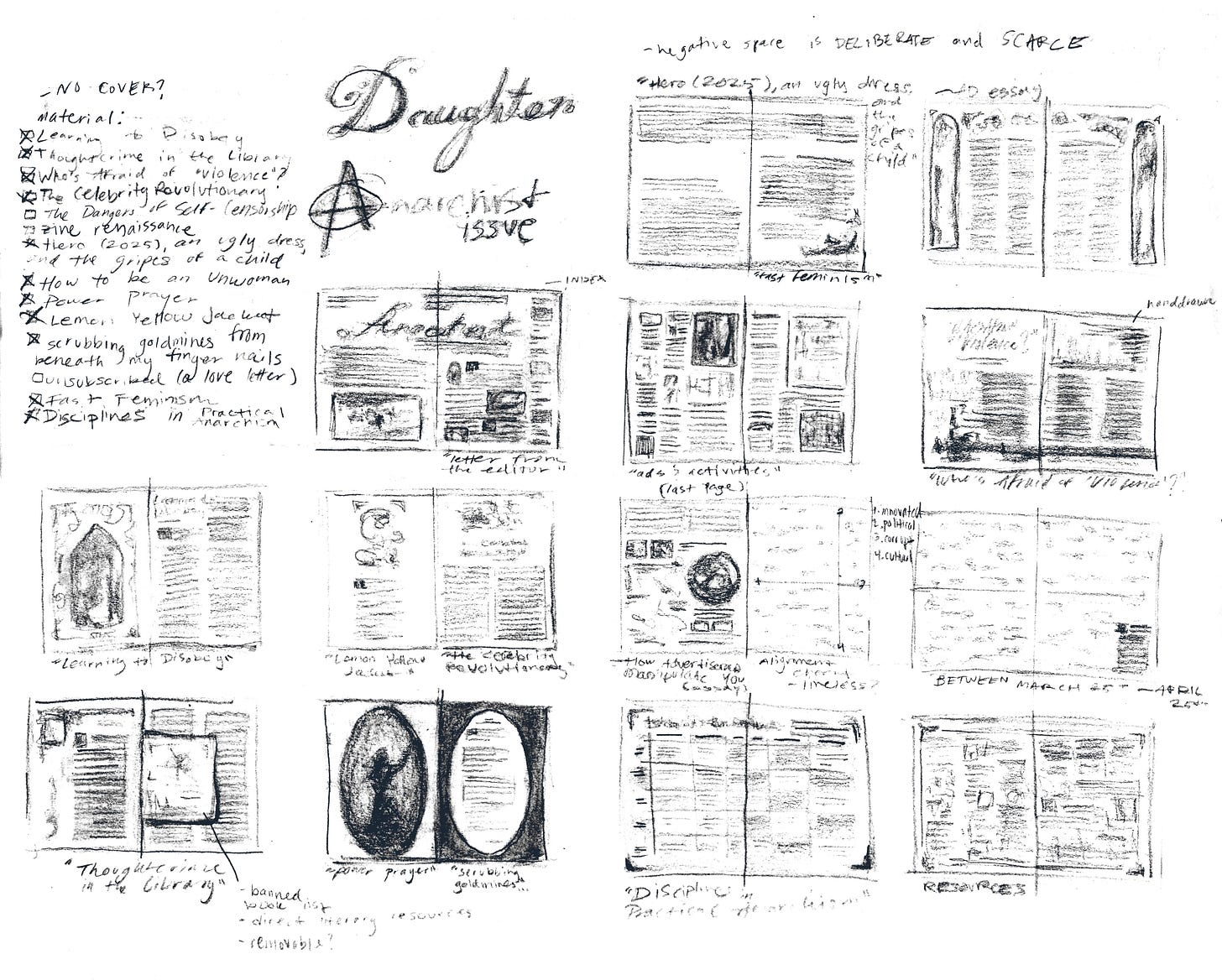

While Daughter Zine draws on imagery associated with girlhood and femininity, it takes girls and their intellects seriously. With the first issue in its archetype zine series called “Anarchist,” it also takes the zine seriously as a medium, at a time when the form has increasingly been co-opted by corporations, startups, and major publishers.

“The audience of girls is really valuable, in that valuing the aesthetic of things is just as important as putting together the information,” Daughter’s founder and editor in chief Grace Anne McKean told me. “If we can just collide those things into something that can awaken somebody or expand their mind in a way that can lead to more empathy and more critical thought, then that’s sort of the goal. And I think that’s really the goal of any kind of modern zine-maker.”

Below is my conversation with Grace Anne McKean, founder and editor in chief of Daughter Zine, edited for clarity and length.

PHONE TIME: Hi Grace! Tell me a bit about your background and how Daughter Zine started.

GRACE ANNE MCKEAN: I have a background in editorial, art, and illustration, and that’s what I wanted to do for my career for a really long time. I had all of these qualities and values that I wanted to represent myself by as an artist, but I didn’t really understand how to do that while working under somebody else’s brand or magazine. So that’s how Daughter started.

Daughter pairs that kind of hyperfemme, pink and girly aesthetic with the very hardcore feminist critique and publishing. It’s a very nice paradox that we balance between. It was really a feminist magazine for friends. But I think of Daughter as like a monolith, in the same way that Charli XCX’s ‘Brat’ was. It’s not so much definable, but it’s sort of you know it when you see it.

PHONE TIME: How do you go about putting it together—on Substack, and then print and digitally?

MCKEAN: It’s kind of simultaneous. Before we had a biannual issue, which is still going on, which was more themed. We had “Devotion” and “Metamorphosis”—very vague, obscure themes.

Our newest print edition, which will be every other month, is much more political. The theme every month is archetypical. So like, what does the contemporary anarchist look like through our eyes? And then our next issue is going to be “Martyr.” So what does the contemporary martyr look like, both from our Western point of view and with everything happening in Palestine right now.

As for the online blog, it gives us the opportunity to play with all kinds of things that are outside of the thematic scheme.

PHONE TIME: I know Daughter publishes across different forms of writing, which seems like a very intentional choice.

MCKEAN: Yeah, we do poetry, essays, short stories. I have a background in poetry, so I knew I wanted to include that. I like magazines that publish fiction next to nonfiction. We’re sort of pivoting right now into a more essay-heavy direction, because it’s like the hot thing right now with Substack kind of blowing up.

But I really love the idea of widening a space for critical thought that doesn’t require a hook or a quick summary to draw an audience in. It’s a lack of trust in the audience that I don’t really like, and I think a lot of young women can see through instantly.

Being a zine online right now is like half marketing and half anti-marketing.

“We exist in a time where art is expected to monetize itself immediately. Where algorithms erase nuance. And where media—especially media led by young women—is expected to serve commerce first and community second. Zines refuse all of that. Zines linger. They imprint. They live in pockets and on bedroom floors and in the backs of notebooks. They are handmade and often badly photocopied and that is part of their magic.” — Grace Anne McKean, “daughter diaries #6: zines are the opposite of algorithm”

PHONE TIME: You mention what it’s like to run a zine online these days. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the purpose of zines within today’s media, political, cultural, and feminist landscape.

MCKEAN: I think about this all the time, and the ebbs and flows of what media looks like on a grassroots scale. Because zines were really huge in the mid-to-late ‘90s, and then sort of faded into obscurity again. Rookie [by Tavi Gevinson] kind of brought it back, but that was mostly an online project. And I wouldn’t say most people consider that small, as they would for many of the niche zines right now. I think of Dreamworldgirl Zine. It’s popular, but they’ve remained small in a way that I really like.

I think people are returning to print from something as cold as the online information sphere, and returning to something you can hold, that you can keep on a bookshelf, that you can carry around with you. Especially as we dig into this accessory-as-identity period, I will take something loaded with information as an accessory versus, you know, a charm.

The audience of girls is really valuable, in that valuing the aesthetic of things is just as important as putting together the information. If we can just collide those things into something that can awaken somebody or expand their mind in a way that can lead to more empathy and more critical thought, then that’s sort of the goal. And I think that’s really the goal of any kind of modern zine-maker.

PHONE TIME: Daughter’s Instagram also captured my attention very quickly. It’s almost like a piece of art you’re making—with the white background and color scheme. But there are also elements that I would say are like memes.

MCKEAN: Daughter really wasn’t a thing until I made the Instagram account. I hate short-form video, and I hate making it. I just don’t have the mind for that kind of marketing thing, so we couldn’t go to TikTok or anything like that.

And I wanted to speak in images. I think sort of the most exciting thing about being alive right now is getting to speak with images in a way that I don’t think has ever really been done before, as casually, and memes are a part of that. I mean, if you’re going to talk about the contemporary experience of girls, meme culture has to be a part of that.

I think memes are beautiful. I love Sotce’s, particularly. I think what she’s done has kind of changed most of women’s interaction with this kind of media and putting themselves out there in this tweet format, but it’s paired with imagery.

PHONE TIME: One of the things that drew me to Daughter was in contrast to all of these “girl trends,” the Barbie movie, stuff like that. It’s not that they don’t have value, but in my perspective they lack feminist critique that’s grounded and historical.

MCKEAN: I don’t really enjoy the idea of as long as women get free rein to make whatever choices they’re doing, then it’s inherently feminist. At the end of the day, at least if we’re talking about mass-marketed stuff, a lot of it’s boardrooms. Maybe there’s like three women in there.

That also means plastic surgery and doing all these things to make you look traditionally good so you can have “pretty privilege.” And doing things to keep yourself ignorant from certain things.

There’s an underlying message to all of these things that very powerful women are doing that aren’t really being talked about. With Taylor Swift, I just think that what she could have done for young women with her following is completely underused. I think if someone like her got up and stood up for something like the freedom from genocide, for example, that would be huge. I also don’t think that celebrities should be [who we look to] as activists. But if we can lock into what appeals to pop girlies or hyper feminine organizations, we can then turn it on its head and educate people. I just see a lot of people with the opportunity to do that, and them not doing it, which sucks.

PHONE TIME: Another thing I’ve been thinking about is the radical potential of zines. Earlier this year Pitchfork announced a zine, and a lot of people were like, “Okay, you’re backed by Condé Nast. Like that’s not a zine.” And there’s a lot of tech-adjacent zine projects. How do you engage with these themes of radicalism and co-optation?

MCKEAN: I recently rewatched the FX documentary series “Mrs. America,” which kind of gave the introduction to Ms. Magazine and everything they were doing. The show kind of portrayed it as this functioning, up-and-coming in stores magazine, but they had to answer to advertisers and fight really hard to get things published with their advertisers.

I don’t ever want to be asked to change anything by an advertiser, and I have a violent distrust towards advertising in general. So I think that roots us in some sort of radicalism. There’s so many brands that really want to get their hands on what young up-and-coming artists are doing. I think maybe half of people see through that, and then half buy it anyway.

We have a staff of 30 volunteer writers and editors, and it’s all very hands-on. I have an eye on almost every draft that gets published. It’s very malleable. And I think that the second you have to answer to a power that you don’t necessarily believe in, that just gets taken away.

PHONE TIME: Daughter’s first “archetype” zine is called “ANARCHIST.” Tell me a bit about it.

We wanted to start with ANARCHIST. This one came through mostly assignment-based essays. I wanted to cover the idea of radical education, which I handed to Sumaiya Fazal, who is an education and philosophy major and is specifically qualified in radical feminist practices. She brought it to life by digging into her own experiences with radical education and what it means to be radically educated online, her experience with Tumblr, and how discussions on social media introduced her to scholars like Edward Said.

Lily Barmoha is our sort of resident cultural celebrity critic. I wanted to give her this specifically, because we’ve had many, many conversations about Taylor Swift alone. She talks about what celebrities used to risk when they used to out themselves as activists—people like Nina Simone. But then you see someone like Taylor Swift, who has all of the means and publicity and “right values” to promote something, and the best she can do is a music video that has rainbow colored sets and Ryan Reynolds in it for some reason.

That is paired with an element in which you can map 22 examples of celebrity activism in 2025. And there’s a little map where you can sort of decide whether it’s tokenistic, transformative, harmful, helpful. In the way Instagram lays these things out, you see a celebrity posting their solidarity about something online next to something like [Gaza Freedom] Flotilla. I just wanted to give people an opportunity to be a little more discerning.

We published a preview of “Who’s Afraid of Violence?” by Yaa Mensah-King on Substack. That’s sort of the most relevant right now, is just the language around violence and the media coverage around it: the question of “Who gets to call it violence, and who gets to enact it?”

When you pair young, smart women with these sort of issues, and also the opportunity to research these issues and correlate critical thought within that—I think we have a very nice dynamic in which it’s sort of rewarding for everybody involved. Anything that can promote critical thought and more words in people’s hands is, I think, important.

You can find Daughter Zine on Substack and Instagram.

More reading on zines, print media, girlhood, and the internet

Mentioned by Grace Anne McKean in this interview:

From PHONE TIME:

Material Grrrlz is building a fiber arts community through memes, meetups, and a magazine

This newsletter features a conversation with Alexa Kari, the founder of the fiber arts community Material Grrrlz. The community is both online and offline, in…

Amy Burek on her publishing project Awkward Ladies Club, zine-making, and the joys of internet forums

Amy Burek is a scientist, artist, and the creator of the publishing project Awkward Ladies Club. She’s also a co-founder of Chute Studio, a collaborative risograph studio in Oakland, California. I first came across Burek’s work …

My previous reporting:

“NYC Feminist Zinefest offers feminist camaraderie and activism” — Columbia Spectator

“Still fit to print: The evolution and future of print media at and around Columbia” — Columbia Spectator

Zines—which are commonly associated with the punk scene but also connect back to the “little magazines” of the Harlem Renaissance—often platform marginalized perspectives absent in traditional media. The 2024 Feminist Zine Fest was hosted at Barnard for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic: Zines addressed topics including racial equity, disability justice, and Palestinian liberation. While much of the zine community has moved to social media, particularly Instagram, excitement for the physical medium has persisted.

Kelsey Russell, TC ’24, is known as a media literacy influencer on TikTok, where she posts videos of herself reading articles in print newspapers as well as other media commentary. Russell said that when she was reading print, she felt as though she was more curious about the news she was reading and would feel less anxious about the news landscape, as opposed to when she was consuming news digitally.

According to Russell, print has the potential to be an accessory, drawing a comparison to Apple’s creation of “products that look good,” which spoke to an interest in aesthetics characteristic of younger generations.

“I feel like with print media, I could see it serving as the new accessory for younger people that says ‘Hey, I’m here to learn. I want to carry this around, have something on me that I can consume information,’ especially just for a generation that likes the happenings that are picturesque,” Russell said.

Elsewhere online:

“Your Next Coffee Might Come With a Zine” — Meghan McCarron, EATER

“The Demise of ’90s Feminist-Zine Culture” — Samhita Mukhopadhyay, The Atlantic

“Feeld, the Polyamory Dating App, Made a Magazine. Why?” — Kaitlyn Tiffany, The Atlantic

“POV: The cool factor of zines draws brands, and hurts publishing” — Ione Gamble, It’s Nice That

“If Conde Nast Can Make a 'Zine' Then the Word 'Zine' Means Nothing” — Adlan Jackson, Hell Gate